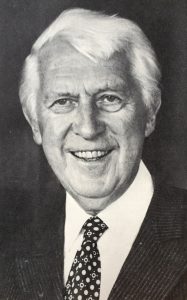

Trygve J.B. Hoff (1895-1982)

A Founding Member of the Mont Pelerin Society

“Liberalism is a formidable vital force, so easily aligned with human nature, with all its qualities and deficiencies, that even the many obstructions placed in its way have never completely succeeded in stopping its functions.”

– Peace and The Future – The Road to Liberocracy

Sometime during the late summer of 1946 Friedrich Hayek flew from Mexico City to Oslo, after a meeting with Ludwig von Mises, to discuss with Trygve Hoff the setting up of a society of liberal intellectuals, later to be named the Mont Pelerin Society. Mises and Hayek both knew Hoff from his book on the socialist calculation problem from 1938, later published in English in 1949 with the title Economic Calculation in The Socialist Society. Hoff’s book was both a theoretical work, building on the theories of Mises and Hayek, and a summing-up of the debate. The book received favorable reviews in American Economic Review, Weltwirtschaftliches Archiv, and even from a socialist leaning economist like Henry Dickinson in Economic Journal.

In Norway Hoff had already experienced a most extraordinary dialogue with the head of the economics faculty at the University of Oslo, Ragnar Frisch, who was a very outspoken socialist economist with extraordinary high ambitions on behalf of central government economic planning. After receiving a copy of Hoff’s book, Frisch immediately advised Hoff to send in the manuscript as a doctoral dissertation. Indeed, Hoff defended his dissertation with Frisch as his opponent for a can-packed auditorium November 25, 1939. Frisch’s main counterargument was that Hoff could have benefited from a more formal mathematical exposition of his ideas.

Before Hoff wrote the book on the socialist calculation problem he had already acquired the ownership of the business weekly Farmand in 1935. Farmand was to become the leading Norwegian business and current affairs magazine of his time. Hoff’s ideal model was The Economist, and this was clearly indicated in the editor’s positional statement from 1935, written in the middle of the depression and surrounded by new and old ideas about “more rational economic planning”: to be an independent voice in the battle of ideas, standing up for economic freedom, personal freedom and freedom of expression. Before he became Farmand’s owner and editor, Hoff had practiced several years of investment consulting and had been writing a regular column on economic policy issues for the left-liberal daily Dagbladet since 1920. After graduating with a degree in economics in 1916, he travelled to France; then later to the United States, where he studied banking and finance and worked on Wall Street.

Going back to the discussions leading up to the founding of the MPS in 1947, we now know that not only did Hayek visit Hoff in Oslo to discuss the idea and possible concepts, but Hoff also met Mises, Jacques Reuff and Leonard Read in the autumn of 1946, where they were lecturing at Read’s newly founded Foundation for Economic Education in New York, and other institutions. As Jörg Guido Hülsmann writes in his Mises biography, “One likely subject of discussion was Hayek’s plan for an international society of classical-liberal scholars.” It should only be added that Hoff showed much more enthusiasm for the idea than Mises did, at least at this early stage. It is also interesting to note that Mises in later correspondence with Hoff showed that he had the highest opinion of the Norwegian economist and editor, and for at least one good reason. Hoff based his economic reasoning very much along the lines of the Austrian School, and he made this quite explicit in many of his articles in Farmand over the years.

Hoff also shared many of Mises’ and Hayek’s perspectives on liberalism. This was clearly reflected in Hoff’s great liberal manifesto, written during World War II, and published immediately after liberation in 1945. This great book of 500 pages contain many parallels to the contemporary analyses and discussions found in Hayek’s The Road to Serfdom, Mises’ Omnipotent Government, Röpke’s books on The Social Crisis of Our Time and The German Question, but perhaps most of all in Walter Lippmann’s Good Society from 1937. At the time of writing, Hoff had already read Lippmann’s book with great interest, judged by the many references. Hoff was not present at the Colloque Walter Lippmann meeting in Paris in 1938, but he evidently had read the notes (the “Compte Rendu” in French) from the meeting carefully, and came out expressing special sympathy with the liberal renewal-thinking of Alexander Rüstow and Wilhelm Röpke, based on the transcript of their contributions.

Unfortunately, Hoff’s liberal manifesto from 1945 was never translated into any foreign languages. If it had been, I am sure that many more would have appreciated the profound knowledge and cultural, social and human understanding that characterized this unusual Norwegian liberal economist. Trygve Hoff was a man of high standards of integrity and he was fearless in his fight against authoritarian and totalitarian forces of all colors. It was no accident that Farmand was the first press organ to be “forbidden forever” by the occupying nazi-regime, in 1940, and that Trygve Hoff was imprisoned for his “dangerous political views and influence”. Amazingly enough, Trygve Hoff still managed to write parts of the manuscript for his liberal manifesto under extreme anti-liberal circumstances, under imprisonment at the Grini prisoner camp just outside Oslo.

As far as I know, Trygve Hoff never willingly missed a meeting of the Mont Pelerin Society, and he seemed to be on very friendly terms with most, if not all, of his fellow founding members. Most importantly, Hoff never tired of referring to these meetings in Farmand, and personally, I can still vividly remember how stimulating it was to be exposed to guest columns written by famous MPS scholars such as Ludwig von Mises, Wilhelm Röpke, Milton Friedman, George Stigler, Henry Hazlitt and many others.

And of course there was Hoff himself. He wrote so many insightful and thought provoking articles on economic policy issues, and he was the strongest voice in Norway arguing against intrusive state interventions and the delusions of central planning. For Hoff this was never only about the market economy, free trade and economic freedom in general. It was ultimately about something of much more profound importance: individual freedom and human dignity.

Trygve Hoff was not only an economist and editor, but also a cultural personality. Sometimes this came out, also in the middle of a book on political philosophy, like in these lines, cited from his book on liberalism from 1945 (my translation from the Norwegian original):

“We are well advised to acknowledge that human beings are not necessarily good.

Not only good. Not bound to be good by nature.

We humans must strive to be good.

We must fight for human dignity.

De dignitate hominis.”

Text: Lars Peder Nordbakken